The Appeal of a Popular Vote

Every vote should count equally, right? It’s an emotionally satisfying idea: the candidate with the most votes ought to win. This straightforward vision of democracy—often summed up as “one person, one vote”—is powerful, and it’s why many Americans have called to replace the Electoral College with a national popular vote for choosing our President. Their perspective is understandable, especially after elections like 2016 where one candidate won millions more votes nationwide yet still lost the presidency. On the surface, a direct popular vote seems the fairest way to honor the will of the people.

The Founders’ Balancing Act

The Founding Fathers in 1787 deliberated extensively on how to craft a fair system for electing the President. They did not choose a direct popular vote for the presidency—not because they rejected democracy, but because they wanted to balance it with federalism, the idea that the United States is a union of individual states. The Electoral College emerged from those debates as a careful compromise, designed to ensure that no single region or densely populated majority could dominate the others in selecting a President. Delegates from large and small states found common ground, giving each state a voice in the process rather than relying solely on a raw national headcount of citizens. In practice, this means winning the White House requires a candidate to build broad support across many parts of the country, rather than simply racking up votes in the most populous cities or states.

Majority Rule and Its Limits

For a moment, imagine the U.S. elected its presidents purely by a nationwide popular vote. Campaigns would logically pour their energy into the biggest population centers—major cities and densely populated states—because that’s where the most votes are. After all, why spend time addressing concerns in rural Wyoming or North Dakota if massive turnout in Los Angeles or New York City could clinch the presidency? It would be like a concert where only the loudest instruments get to play—sure, you’d get volume, but you’d lose the harmony. Over time, the interests of smaller and less populous regions could be completely drowned out simply because they don’t have the numbers to compete.

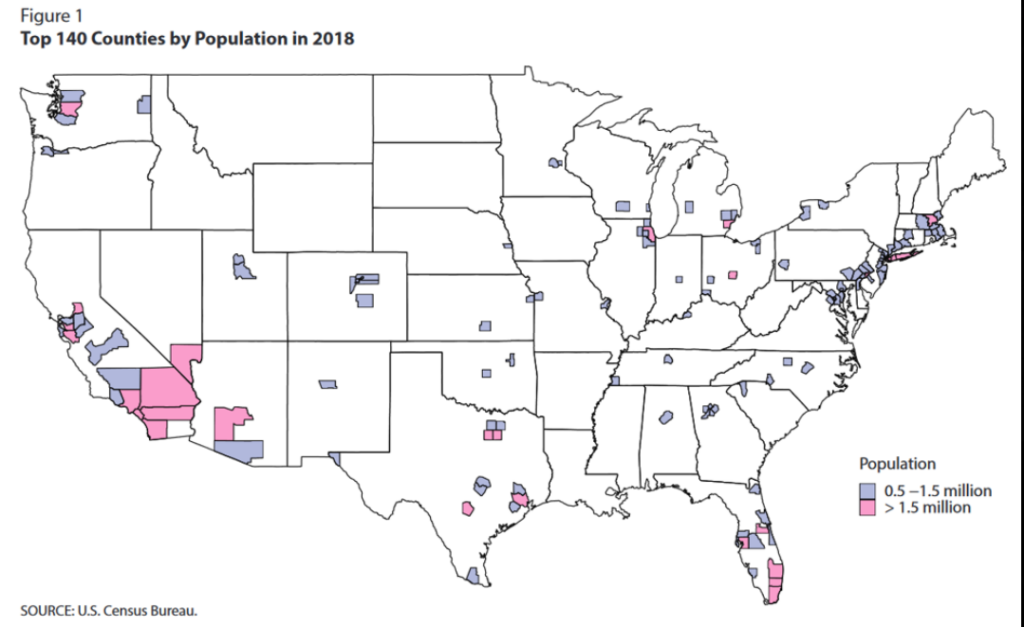

This map highlights the 140 most populous counties (shaded) which contain about half of the U.S. population. Notice how concentrated those areas are, especially along the coasts and in a few inland hubs. If winning the White House simply came down to a raw vote total, a candidate could focus almost entirely on these dense urban and suburban areas and still succeed, leaving the vast unshaded expanse—home to the other half of Americans—largely sidelined. The Electoral College counteracts this by compelling candidates to seek support across a wider geographic range, bridging the interests of both metropolitan and rural communities.

In fact, the Electoral College provides some underappreciated benefits that a straight popular vote would lack:

- Prevents Regional Domination – Without the Electoral College, a few heavily populated regions of the country could effectively decide every election, while smaller states would have virtually no voice.

- Encourages Broad Coalitions – Because victory requires winning many states, successful candidates must appeal to a variety of communities and interests nationwide, not just to one demographic or one megacity.

- Protects Minority Interests – By avoiding a simple majority-rule sweep, the system ensures that regional minorities (for example, voters in less populated states or rural areas) aren’t completely overshadowed by one large national majority.

Preserving a Balanced Union

For all its imperfections, the Electoral College reflects a deliberate choice about how to hold together a nation of many parts. It has been a mechanism to ensure candidates build broad national support, rather than catering only to a narrow majority. Eliminating it entirely would fundamentally change the character of our republic’s elections.

The genius of the system lies in the balance it strikes between majority rule and the federalist principle that every state matters. It ensures a President must consider all Americans—not just those in the biggest cities or most populous states—when seeking the White House. Abolishing the Electoral College in favor of a direct popular vote might feel more straightforward, but it would tilt the scales of power heavily toward urban majorities and sideline smaller states, undermining the very principle of a balanced union that holds this country together. In the end, the Electoral College isn’t about denying the popular will; it’s about tempering it just enough to make sure every corner of America counts.