by Mark Twain (or a reasonable facsimile thereof)

I have known many men in my life — some great, some grotesque, some merely good at poker — but none so unexpected in his excellence as that magnificent apparition known as Chester Alan Arthur, the 21st President of these United States and, I daresay, the best-dressed surprise to ever stumble into the Oval Office.

When Mr. Arthur first appeared on the national stage, he was thought to be little more than a well-tailored marionette dangled by the greasy fingers of New York’s political machine. He had previously held the post of Collector of the Port of New York — a job that involved great sums of money, a great deal of cronyism, and very little actual collecting. One would not be blamed for suspecting he’d sooner appoint a man to office for pouring him a proper whiskey than for any measurable merit.

Then fate — which is often clumsy, theatrical, and occasionally armed — saw President James A. Garfield shot in the back by a lunatic. The country wept, and Mr. Arthur found himself plopped rather awkwardly into the presidency, much like a cat landing on a slippery table.

And lo! Instead of becoming a figurehead in a fine coat, Arthur did something altogether unseemly in political circles: he became honorable.

Imagine the shock of every party boss and scoundrel in Washington when Arthur backed the Pendleton Civil Service Act, putting an end to the old spoils system that had given rise to his own cushy career. The man turned on his own kind like a well-mannered werewolf — only instead of howling at the moon, he hired people based on exams.

Yes, exams! The very same thing schoolboys dread and politicians avoid.

Now, I’ve seen miracles — I’ve even been to church on time once — but I never expected such virtue to emerge from a man with 80 pairs of trousers. And that is not an exaggeration. The man had more pants than a traveling salesman has excuses. Rumor has it he changed outfits as often as Congress changed its mind.

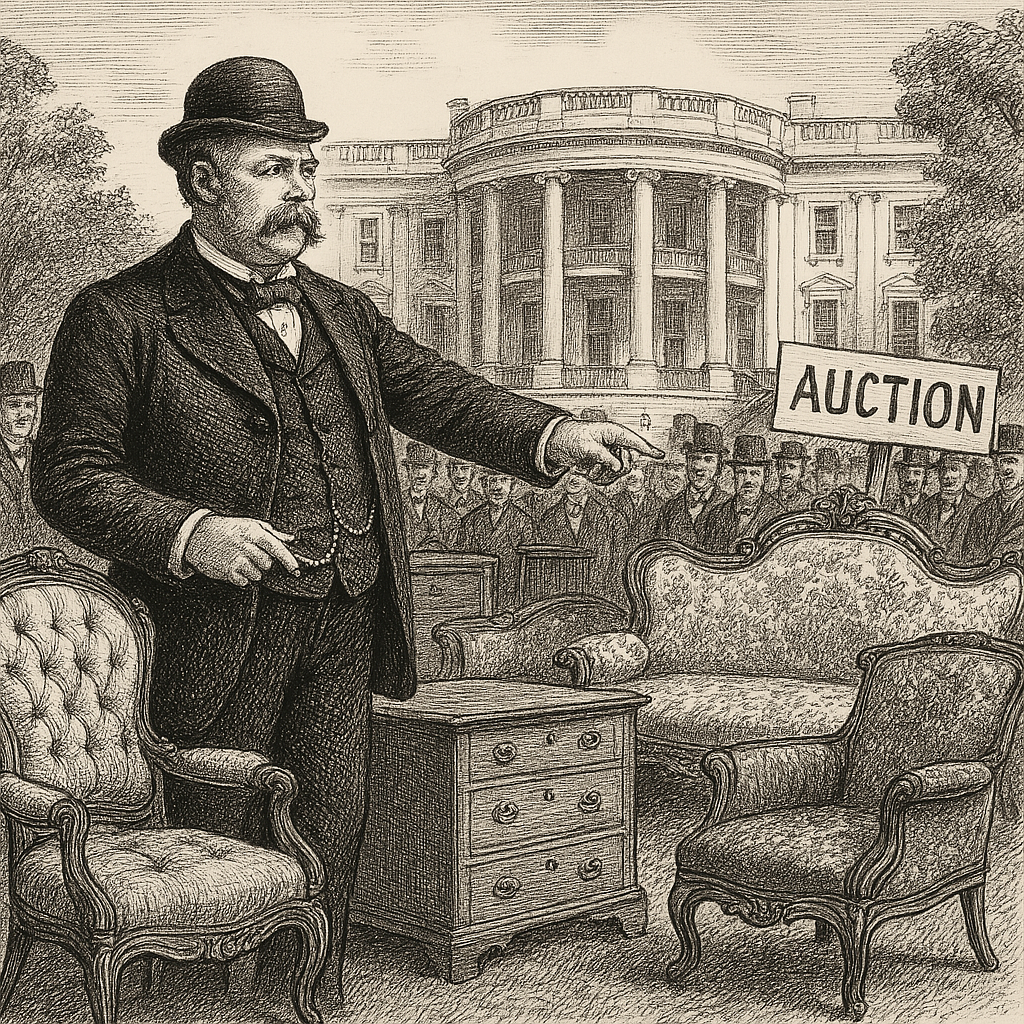

He refurbished the White House with the flair of a bachelor and the budget of a railroad tycoon. He sold off decades of presidential furniture, including a couch that may have once held the posterior of John Adams himself. And in its place he brought velvet, marble, and perhaps a bit too much brass.

Some say he lacked charisma. I say he had it in his mustache alone. That thing had its own opinions and probably its own address. When Arthur entered a room, it was not merely he who arrived — it was the mustache, the tailored coat, the cologne, and then the man himself.

His presidency lasted only a single term, and he did not seek another. Why not? Because the man was dying and, unlike modern politicians, he had the good sense not to make a pity spectacle of it. He slipped out of office with more dignity than he had arrived with — which, for a man of such stunning waistcoats, is no small feat.

So here’s to Chester A. Arthur, the man who proved that a silk cravat and a soul of steel can, on occasion, occupy the same chest cavity.

God bless him — and may his mustache live on forever in the halls of improbable history.

Yours in laughter and mild disbelief,

Mark Twain