Part 1

Part 2

Good day, Americans.

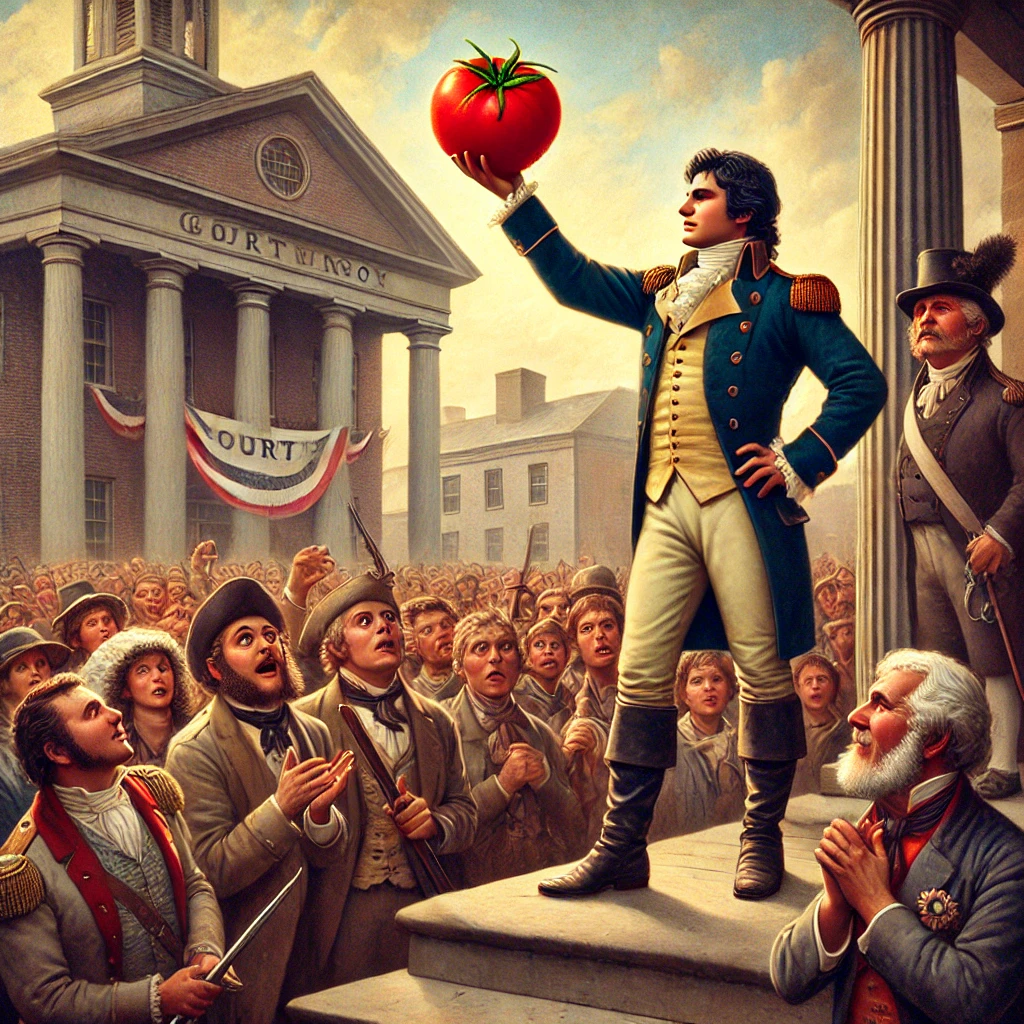

In the bustling heart of Salem, New Jersey, on a sunny September afternoon in 1820, a crowd of curious onlookers gathered around the town’s modest courthouse steps. They murmured with unease, their eyes fixed on a single man standing boldly at the top of the steps. This man—a local landowner, gentleman farmer, and war veteran—had staged an unusual spectacle. A wicker basket sat before him, brimming with ripe, crimson fruits. Or were they something far more sinister?

For you see, in 1820, these fruits were known not as tomatoes… but as wolf apples.

The very word conjured images of danger. They were a part of the nightshade family, a botanical clan that included some of the most poisonous plants on Earth. To touch them was one thing, but to consume them? Madness. Yet, that’s precisely what this man was about to do.

Some in the crowd believed he was attempting suicide. Others thought it a foolhardy publicity stunt. And as he lifted the first glossy red fruit to his lips, gasps rippled through the gathered townsfolk. Women averted their eyes. A child began to cry. One man shouted, “Don’t do it, Colonel!” But he did.

Bite after bite, juice running down his chin, he devoured the entire tomato. Then another. And another. Onlookers waited for him to keel over, to clutch his chest in agony, to collapse on the cobblestone steps. Instead, he calmly wiped his hands, tipped his hat to the bewildered crowd, and walked away—very much alive.

What could drive a man to such reckless defiance of popular belief? Was he simply a madman? Or was there something else at play, something buried in his history, that led to this extraordinary moment?

To understand, we must go back. Back to a dark chapter in European history, and a secret whispered only in kitchens and herb gardens. A secret that shaped not just the life of this man but, ultimately, the future of food as we know it.

Robert Gibbon Johnson was not just a farmer—he was a scholar. And like many gentlemen of his era, he prided himself on keeping up with the latest advancements in science and agriculture. While the people of New Jersey feared the tomato, dismissing it as a poisonous oddity, Johnson had learned of another perspective.

Decades earlier, during the Enlightenment, botanists in Europe had begun experimenting with New World plants, including the tomato. In Naples, Italy, the fruit had already become a staple of the local cuisine, and recipes for tomato-based sauces were spreading across the continent. But these culinary experiments were not shared widely. You see, tomatoes had been tainted by a peculiar reputation among European aristocracy.

It was whispered that the fruit was cursed—a bringer of death. And this reputation stemmed not from the tomato itself, but from… wealth.

The answer lay in the pewter plates of the 17th and 18th centuries. These plates, favored by Europe’s upper classes, contained high levels of lead. When acidic foods, like tomatoes, were served on these plates, the acid leached the lead into the meal. The wealthiest diners, accustomed to eating tomatoes with their extravagant dinners, began to suffer the effects of lead poisoning: seizures, confusion, even death. The tomato was falsely blamed for their demise. It became known as a “killer fruit.”

But Johnson knew better. He had traveled to France, where he had dined on tomato dishes prepared by daring chefs. He had corresponded with botanists in England who confirmed the tomato’s safety. And back home in New Jersey, he cultivated them in his garden, enjoying their bright flavor with every meal.

To him, the idea that his neighbors would fear such a delicious, harmless fruit was absurd. But more than that, it was personal.

You see, Robert Gibbon Johnson had lost someone he loved dearly—his first wife, Juliana, who had died of illness years earlier. During her final days, she had begged him to pursue a life of boldness and truth, to never let fear or ignorance dictate his choices. So, as he stood on those courthouse steps in 1820, tomatoes in hand, it was not just science he was defending. It was her memory.

And now you know… the rest of the story.

Good day!